The St. Louis Beacon features filmmaker Tammy Nguyen Lee and others a part of Operation Babylift in an article discussing life after the war, and what the future holds. Read the original article on the Beacon website.

Lost and found: Some adoptees prepare to return to Vietnam, but others have no desire

By Kristen Hare, Beacon staff

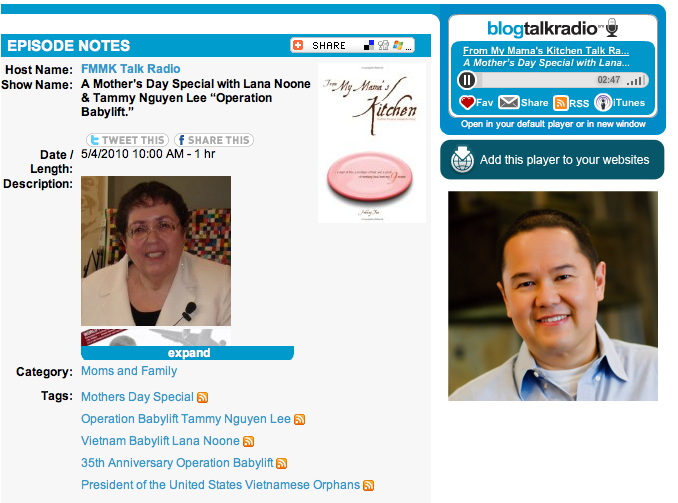

Posted 9:31 p.m. Sun., 03.14.10 – During the time between college and grad school, Tammy Nguyen Lee began volunteering with the Vietnamese community in Dallas. At the time, she helped with the production of a play commemorating the 25th anniversary of the fall of Saigon. The play had something about Operation Babylift.

Nguyen Lee wanted to know more.

“I think why I was originally attracted to it was the fairy tale of what it seemed to be,” she says.

The adoption of thousands of orphans from Vietnam during Operation Babylift seemed like a story of humanitarians joining together to help people. And it was nice to find something so positive.

“It was, for me, this kind of bright spot that came out of the war,” says Nguyen Lee, who is Vietnamese.

She talked with Babylift adoptees over a period of several years, researched and found out more. And the story changed.

“Like every good story, there are layers and complications,” she says. “It wasn’t just one big happy ending.”

Nguyen Lee’s resulting film, “Operation Babylift: The Lost Children of Vietnam,” isn’t a comprehensive history, but rather an opportunity for discussion, she says, and a chance for the adoptees to tell their own stories in their own voices.

Through her research, Nguyen Lee found that each adoptee did have his or her own story, but for many, there were commonalities. Growing up, many didn’t have an Asian support community. “So they grew up kind of thinking that they were white,” she says.

That changed when school started and they had to deal with racism. Around college, many began looking for their own identity.

“And I think that’s when a lot of them started thinking about what does it mean to be Vietnamese,” she says.

Around age 25, many began returning to Vietnam.

“It was like a line that had slowly been drawn into a circle.”

For some, that circle closed when they visited Vietnam and saw the orphanages where they’d been and walked where their birth mothers had walked, she says.

Sister Susan Carol McDonald has seen those moments, which happen on every trip she takes back with adoptees. For many, they’re seeing where they’re from for the first time, like the young man who met a nun who’d cared for him as a child and saw where his crib once sat.

“I think it’s very meaningful to them,” says McDonald, who worked as a nurse at New Haven Nursery from 1973 to 1975. She’s taken seven trips back to Vietnam since leaving.

And at month’s end, McDonald and a group of 11 will meet up with 40 others in Vietnam. Their visit will mark the 35th anniversary of Operation Babylift.

‘I FELT AT HOME’

Five years ago, Lyly Koenig left for Vietnam with Operation Homeward Bound on a World Airline jet, retracing the path back to Vietnam 30 years after leaving as a baby. The Babylift adoptee felt a connection with the country as the plane landed, and again and again during the trip. Once, on a motorbike tour of the city, she looked around and realized she was surrounded by other Vietnamese.

“I felt at home,” she says. “That’s when I felt at home over there.”

One night, she and the other adoptees went out and walked around and ate street food.

“It was comfortable,” she says.

Koenig, who grew up in Festus, didn’t know many minorities growing up. To her, it wasn’t a big deal.

“My parents raised me to be comfortable in who I am,” she says. And if someone made a negative comment, she just blew it off.

Koenig, who is planning a move to California to begin a career as a fashion designer, will join McDonald on the next trip back to Vietnam.

She’s excited to see more of the country. If the opportunity came up, she’d live there, Koenig says. She’d love to teach English or even work with orphans. On this trip back, she’ll see the orphanage where she lived. She hasn’t seen it before and is looking forward to that.

“And seeing where I started and hopefully trying to just learn a little more about my history,” she says.

‘I’D BE COMPLETELY LOST’

Last fall when “Operation Babylift” first played in St. Louis, Mindy Kelpe-Eubanks drove up from her home in Cape Girardeau to see it. For a month or so after, she woke in the middle of the night from bad dreams.

“It brought out some really strong feelings for me,” says Kelpe-Eubanks (right), who is a Babylift adoptee and survived the crash of the C5 Galaxy during the first flight out of Vietnam in April 1975.

Kelpe-Eubanks grew up in Cape Girardeau and has recently returned there with her husband and two children. Like many of the adoptees, she grew up feeling different. And kids in her small, private school reinforced that. For several years, other kids called her a nickname, which she loved. Finally, in the 7th grade, she asked one of them what “Immie Joe” meant.

“It means you’re an immigrant,” they told her. “I thought I was really very accepted, and when I found out what it meant, it crushed me.”

Kelpe-Eubanks watched her daughter, now 19, go through the same struggles. At some point during high school, kids put a green card in her daughter’s locker.

“I’ve had to deal with this my entire life,” she says. “Finding your place in the world is hard.”

Despite those struggles, though, Kelpe-Eubanks has no desire to return to Vietnam. For one, she doesn’t fly. At all.

Also, she knows who she is, she says, and that person’s home and family are all here.

“I don’t want to go over there searching for something that I won’t find,” she says.

Instead, she’s busy with her children, 19 and 5, her husband, and her newest challenge — law enforcement academy.

And while she likes hearing about other adoptees’ experiences in Vietnam, Kelpe-Eubanks says she knows nothing of the culture or language.

“I’d be completely lost,” she says.

‘THEY’RE STILL TRYING TO PUT TOGETHER PIECES’

In the process of making her film, Nguyen Lee found the story of Operation Babylift wasn’t a fairy tale with one happy ending, but a story that was still unfolding — and still needed to be told.

International and transracial adoption has changed, from the way adoptions are conducted to the way people think about what children need.

According to Holt International, international adoptions now can take between one year and three, and cost between $15,000 and $25,000.

At a Vietnamese culture camp Nguyen Lee visited in Colorado, there are now two generations, the Babylift group and a younger group. Their issues and needs are totally different.

But so are the times.

“They grew up in a time when Vietnam was an unpopular subject,” says Nguyen Lee, who is the president and founder of ATG Against the Grain Productions, a nonprofit that focuses on social issues and raises money for orphanages abroad. “The mere mention of it was cause for a lot of grief for people.”

That’s changed, but some things haven’t.

Thirty-five years ago, Sister Susan Carol McDonald knew that understanding where they came from would be challenging for many of the adoptees. Now, she watches them in that process.

“I feel very protective of them,” she says, “and realize that they’re going through a lot of emotions when they go. You know, they’re still trying to put together pieces of their early life and make some sense of what happened.”

McDonald leaves for Vietnam on March 31. After this trip, she knows she’ll return again.

Tammy Nguyen Lee at filmAsiafest in September.

Tammy Nguyen Lee at filmAsiafest in September.